Today is an exciting day. Not long ago, my wife returned home with a trunk full of books: the legendary World Book Encyclopedia. This was the reference material of my childhood, and my first point of contact when I found myself plagued with questions, insomnia, or snow days. If it wasn’t in The World Book, it probably wasn’t worth knowing.

Today is an exciting day. Not long ago, my wife returned home with a trunk full of books: the legendary World Book Encyclopedia. This was the reference material of my childhood, and my first point of contact when I found myself plagued with questions, insomnia, or snow days. If it wasn’t in The World Book, it probably wasn’t worth knowing.

I learned about all sorts of things here: how cheese is made, why soap works, how cars are manufactured, where kindergarten came from, why alternating current is chosen over direct current for distribution over long distances. Some time after I left home, my parents gave the encyclopedia to another family.

These days, unless I’m doing research for an academic paper, most of my questions are answered here, or here. The Internet has changed everything. I’m an advocate for Wikipedia, even in [some] academic settings: after all, the organic and community-reviewed site’s accuracy has been compared to Encyclopædia Britannica. And why not? Culture and language is in constant transition. Technology and research progress and are distributed so quickly that the value of printed reference material, from encyclopedias to dictionaries, might been called into question. If I’m at the grocery store, and I feel a sudden urge to know more about the business practices of Nabob, I can find the information I need. Instantly. If I’m lying awake in bed, wondering what the creepy insects showing up near the back door are, I can find out. Instantly. These things can, and do happen. Often.

But truth be told, I’ve been after a set of World Books for some time. Why? Chalk it up to age, nostalgia, and my new role as a parent: books like these were important to me, and I hope that on some level, I can share them with young Eben as he grows up. But it would be naïve for me to to think that the 1986 World Book Encyclopedia could play the same role in his life that it did in mine. I knew that, as I carried them into the house. And I knew that, as I flipped through a few volumes, recalling some of the articles and photographs from the world of my youth: “Automobile,” displaying a Datsun 280ZX; “Soviet Union,” see Russia; “Russia,” a Communist dictatorship of 15 Union Republics; “Chernobyl,” no entry. Really?

In the 1987 Year Book, I found a black-and-white photograph, and a one page article titled “Explosion at Chernobyl”.” And what I already knew became crystal clear: these books captured one point of view from a moment in time. And while they will be useful for teaching my son about reading and learning, as well as topics like stars and bugs, entries like the ones listed above will need to be interpreted through the lens of “the world my dad grew up in.” What a young Jesse Dymond once considered catalogues of knowledge have become history books. Useful, but not in the same way. Because it’s not 1986. Perhaps our natural desire to hold these records and experiences up as permanent vessels of that elusive thing we call truth is a form of idolatry?

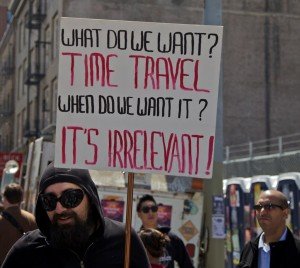

I find myself wondering about our desire to cling to everything from ideas to interpretations, language to liturgy, style to song. The Church is no stranger to moments in time, and rightly so: we relive the last supper almost every time we gather (incidentally, using a prayerbook from 1985). We’re about to move into a season of watching and waiting for Christ’s birth in our world. And these are wonderful moments. Ancient moments. Moments in time that hang in the mystery of already-but-not-yet here. Moments for which time is irrelevant.

I find myself wondering about our desire to cling to everything from ideas to interpretations, language to liturgy, style to song. The Church is no stranger to moments in time, and rightly so: we relive the last supper almost every time we gather (incidentally, using a prayerbook from 1985). We’re about to move into a season of watching and waiting for Christ’s birth in our world. And these are wonderful moments. Ancient moments. Moments in time that hang in the mystery of already-but-not-yet here. Moments for which time is irrelevant.

What do you think? Are some traditions and resources obsolete, and dubiously passed on to the next generation? Are others timeless? How do we know the difference?

By Larry Robertson November 25, 2013 - 6:29 pm

It seems to me that you do something twice in the church and it becomes a tradition. I have started a few. 10, 15 years later the parish is still doing it with out the circumstances that warranted the event. I get blamed for having it even though I have not been ther for manny years. We need to let things die if it’s usage or significance is no longer there

By Afra Saskia Tucker November 25, 2013 - 10:11 pm

I can see how our desire for ‘eternal life’ can get indiscriminately and unsuitably mapped on to all the good things we set out to do. How do we tell what needs to be allowed to die as opposed to reaffirmed? I guess I would ask: how is this (tradition, resource, etc) giving life, why, and to whom? Does it deprive others of life? How can the communities involved best work out these problems so all feel supported and willing to make sacrifices for each other to live and abundantly so? For me, it should always start from the place if Christ-centered intentions, relationships, and actions. Otherwise, how is any of it better than producing, peddling and purchasing designer knockoffs? I think we all deserve so much more!

By Melanie Delva November 26, 2013 - 3:57 pm

This is why we have archives. People think that archives are “the old stuff we have no room for and don’t need”. I would change that to “the old stuff we still need”. Archives bear the imprints of human interaction in the area of time and space and – much like the out-dated encyclopedia – tell us more about the context they came from than anything about what they contain. Without even reading it, a letter between a priest and the “Board of Missions to Orientals” tells me something about the time and context. And we need that. We need it for understanding, we need it for truth, we need it for healing, we need it for resurrection.

By The Rev. Jesse Dymond November 27, 2013 - 9:58 am

Wow! I had a feeling this blog would inspire a diversity of views. And yet, I think I’m hearing a common thread: the practices we hold on to, whether in our words or worship, exist to serve a purpose. If that need is not being met, it’s probably time to rethink the “tradition.” Meanwhile, if it ain’t broke, why fix it?

However, I can’t help but think it’s often a little more complicated that that, especially when it comes to worship. One of the great things about being Anglican is the (albeit somewhat loose) notion that we share in common prayer. And while our prayers and liturgies must speak to the community in which they are practiced, the tradition we inherit still proclaims “lex orandi, lex credendi”: we are shaped by our prayers and creeds, rather than then other way around. The World Book experience has me thinking a little more seriously about where we find the balance.

Melanie, I think your comment adds new depth to the conversation. You’ve given me a new appreciation for archivists! And you bring a certain authority to the table, at least when it comes to “what we do with the past.” Your reference reminds me of Canon XIV, which removed the Good Friday “prayer for the Jews” from the Book of Common Prayer. Can we pretend it wasn’t there? No. How else could we move on?

By Afra Saskia Tucker November 27, 2013 - 4:59 pm

I too really like the archivist’s reminder that the past is needed to acknowledge, heal, and move on. Thanks for bringing that in!

Jesse: while I agree that the prayers are inherited and contain the power to shape us, I don’t agree it’s ‘not the other way around’. I don’t see how there cannot be two directions in the conversation that is prayer, even if we acknowledge an origin or source; I feel this must also take place within the frame of common prayer. But it’s possible that I am misunderstanding what you are trying to say or am just a weird Anglican.

By The Rev. Jesse Dymond November 28, 2013 - 9:09 am

Oh, I agree with you. If I didn’t, I probably wouldn’t read scripture in the English language, nor would I be Anglican. Context is important, and it’s virtually impossible not to read our own culture and experience into the past. I simply brought up the inherited phrase, as traditionally used around things like creeds and the canons of scripture, to remind us that the conversation is two-way: sometimes we’re inclined to throw away babies with bathwater. 🙂

‘Already and not yet’ living is never simple, is it?

By Kyle Norman November 28, 2013 - 3:30 pm

I think part of the discussion is how do we define that which is definitive for the community (scripture, creeds, Eucharist) and what are matter of tradition (the Rector’s wife wearing white gloves as she pours the tea at the spring bazaar).

Not everything that we do is definitive -and some things we are led into for only a season. This doesn’t deny value or worth – it’s just a recognition that as the people, time and culture changes, so too the church must change as well.

After all, if we are to be not just resurrection people, but also eschatological people, part of the question must be: Do we live in the presence of the future or the maintain of the past?

By Dell Bornowsky December 1, 2013 - 1:46 am

Our quest for contemporary relevance and significance in our traditions is admirable and is itself a worthy tradition. (Such diligence is evident in our Anglican formation: “Of ceremonies, why some be abolished and some retained.” )

Afra, I agree our desire to be eternal sometimes balks at letting temporal things be temporal. And I suppose allowing things to die is part of accepting our own finite creatureliness.

Kyle, I agree that one place to determine the value of a practice may be whether it is “definitive for the community”. On the other hand I am not sure we will always know what (should) define us. Unlike existentialists and humanists who only have their own choices by which to define themselves, as Christians we see ourselves as creatures and since our very personhood (both individual and corporate) comes from an inscrutable god, we are likely defined by more than we realize. When I am startled to hear myself say things just like my father did, and when my wife notices that my son walks the same way I do, I realize that much of what makes us who we are is not our deliberate self defining choices but much more intangible continuities with the past.

Jesse, perhaps like you I am also questioning the common thread you identified (“the practices we hold on to …exist to serve a purpose. If that need is not being met, it’s probably time to rethink the “tradition.”) I am not sure it is safe to assume we will always know all the purposes of practices and traditions we hold or whether a “need” is being met; anymore than being safe to assume that since I haven’t had a flat tire all week: carrying a spare is a useless tradition. The rabbis used to say that each portion of Torah has 70 meanings, but that each meaning won’t be comprehended until the circumstances arise which need it. Perhaps we should keep traditions not just for what they accomplish in the present, but for the unimaginable things they will accomplish in the future?

By gacb December 11, 2013 - 11:44 am

Even though I’m a lifelong (past a half century) Anglican, sometimes I wish the BAS/BCP would disappear from the pews and we just ‘wing’ a service that makes sense of the gathering and why we are here in the first place.

Listening to people mumble the same prayers each week makes me wonder if it’s part of the reason the church is getting greyer and greyer.

By Tony Houghton December 11, 2013 - 6:34 pm

I have been in churches that “wing it” and there’s a lot of bad liturgy ,if you could call it that ,and bad theology.I Am not saying that the BAS is much better it is peppered with bad theology as well. BCP has lasted for centuries ,by and large, and is one of the most theologically sound prayer book of the lot of them.I too have been in the church for over fifty years and have had people from other denominations comment how sound BCP is.There is a move in a lot of the Presbyterian and Evangelical churches to move toward having more liturgy and moving away from “winging it” because there is more substance there.

By Dell Bornowsky December 17, 2013 - 12:32 am

I spent most of my life in churches where we just “winged it”. It was never long until that became our expected liturgical form –the ritual of “just winging it”. It occurs to me that rituals and liturgical traditions are like containers that may be either full or empty of meaning and wholeheartedness (or somewhere in between). The danger of “empty ritual” is real, but is it safer to not have any ritual that even could be filled with meaning?

A friend told me that in his tradition, communion was deliberately rare so it wouldn’t become too familiar and lose its significance. I wondered if the same logic should apply to hugging my child or telling my spouse that I love them, or going to work or eating supper.

What is the solution to the problem of absent-mindedly “going through the motions”? Is it the discipline of being mindful and wholehearted or should we abandon even the motions?

I believe wholehearted worship will seek ways to express itself that are both old and new, both routine and spontaneous. I think good liturgical practice makes room for both. Perhaps once in a while Anglicans should “wing” a service. It might help us appreciate the purposes of both containers and contents.