For God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength. He is the source of your life… Christ Jesus. –1 Corinthians 1:25, 30a

For God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength. He is the source of your life… Christ Jesus. –1 Corinthians 1:25, 30a

It is getting so loud. I don’t know about you, but I can barely stand it. Social media, facebook, the radio, the news… You know what I am talking about, and I can’t help myself. I am offended, affronted, outraged. I can’t turn my head the other way.

You can’t shout louder, the noise is just too high.

Is it the language of objectification of other human beings—Muslims, Mexicans, Syrians, Iraqis, those others, or those nasty women? This betrays a posture towards life that is completely self-oriented, a universe that is just a field of objects that are there in the service of me. Anything has value only in relation to me. Me! Me! Me!—The wisdom of the world.

It is just so loud, and so obnoxious. It grates at me. Maybe that’s because I know I participate in such a vision, and I am being called out… it strikes at the heart of the Gospel.

So how about this word: other. From a grammatical point of view, consider the distinction of subject-object: “the fox jumped over the fence.” Fox, subject. Fence, object. I saw the horse. I: subject. Horse: object. Experientially, when I experience this world, me is always the subject, and you, the other, is always the object.

This is how we describe, speak of, and experience our world and our relationships. We each live in our own little worlds, as subjects, relating to everything around us. And, things take on their meaning, or value, only in relations to me, the subject. Other people, even, become objects in our fields of awareness, assembled into categories, according to my purpose. It is amazing to think that here is I (subject) addressing you (object), and behind your other-ness, as my object, there is an :I-ness: you are a subject. You are a me, and the person sitting next to you is another subject, another me, within whom is a unique beautiful world, being, awareness, and vast landscape of reflection and life—a need to be loved, to belong, fears, wounds, joys—all the things that make up you as you. We are each a room full of images of God: subjects experiencing everyone else as objects.

Take a moment to imagine and visualize yourself taking a stroll downtown. The sun is shining. You’re, maybe, on your way to a nice lunch with friends when up ahead, you see a panhandler. He is sitting on the ground, holding up his cup asking for money. You still have time: there are a good 10 people ahead of you. What is going through your mind? What is that uncomfortable feeling? Do you get your phone out to appear busy? Or start ruffling through your handbag so you can pretend you did not see him? Do you cross the street? But that moment comes, and despite your best efforts, he sees you. Your eyes meet. He asks, ”spare some change for the strange?”

Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre would suggest that in that moment we are given a great opportunity, if we are aware of it. Because up until that moment, that person is just an object. A bum. A panhandler. An object in my sea of objects in the kingdom of me—an object of my own making: my projection, and the object of my subjectivity. The other becomes really other, suggests Sartre, only at the crucial moment that I am seen by the other.¹

When I move beyond just seeing the other and allow him or her to see me, then the other leaves the realm of a thing amongst other things and regains his or her status as a subject in relation to and in communion with me. In the moment of being seen by this other, I realize that that other is another subject, another me, another “I am” looking back at me as his object. We experience the other when we are seen by the other.

The other profound gift of this encounter is that we not only experience the other as a subject, but at the very same moment, we discover ourselves. The unidirectional monologue in our heads describing this sea of objects and experiences is suddenly disoriented, and we are now held accountable, raw, and vulnerable as we find ourselves under the horizon of this other. We are both subject and object: we encounter the Christ in the other at the same moment we find Him hidden within ourselves.

And this, friends, is how we experience the great Other: this mystery, ultimate reality, God. We cannot know God, or life, for that matter, as an object. We can only know God—only know the truth, when we allow ourselves to be seen. When we find ourselves under the horizon of this Holy Other.²

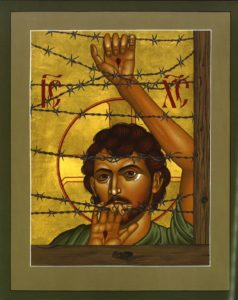

This is why we worship, and why we pray. We become who we are by placing ourselves under his horizon, orienting ourselves to other. This is how we are to pray with Icons, for example. Far beyond a picture on the wall, we are to place ourselves under the gaze the vision of God. Our worship is filled with beauty, with awe and mystery, because it leads us away from objectification, and leads us into wonder, where that which we seek is always just out of reach until we discover it is we who are the ones being grasped.

We are grasped, and beheld, and blessed. Blessed because he is our very life, and our blessedness comes not by our power and strength, even our virtue and piety, but in our consent, our yielding to him, the source of being.

This Christian life is not a solo project: we need each other. We need the other to be who we are. My humanity is bound up in yours: to be me, I need you, for we can only be human together.³

It is in this spirit that we hear the beatitudes: the beatific vision that names what true blessedness is. This is the manifestation of Christian life, the virtues of the saints, the reality of life lived in the fullness of our truest nature and humanity. The wisdom of the world, a world oriented to me alone, is a demonic wisdom that leads us only to death. The foolishness of God is dispossession of self, in the face of the other, loving at our own expense, filled with He who is our very life. The Beautitudes relate the ontological state of kenosis (self emptying), in which blessedness is bestowed upon those who claim their “object-ness”, in relation to the Holy Other, the true subject. By so doing, we paradoxically gain all, for our life, our being is found in Him alone, we claim true personhood as created—made in the image and likeness.

Try reading these words in a deliberate whisper. Maybe a few times, with lots of silence in between. Maybe with someone, together, but to yourself. In fact, read them to your most inmost self, where he who is the source of your life dwells. Remember those huddled in airports, or refugee camps, or Syria and Iraq whispering these holy words of salvation. Amidst the clamour and barking and loudness of the world, say together this foolishness of God, together using only a whisper and then, enter into God’s first and greatest language: silence.

When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up the mountain; and after he sat down, his disciples came to him. Then he began to speak, and taught them, saying:

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. “Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. “Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy. “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. “Blessed are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for in the same way they persecuted the prophets who were before you.

– Matthew 5:1-12

¹Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness. trans. Barnes, H. (New York: Washington Square Press, 1956), 21.

²Insight drawn from John Panteleimon Manoussakis, God after Metaphysics: A Theological Aesthetic (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007)

³Attributed to Desmond Tutu.

By Patricia Fisher February 4, 2017 - 9:47 am

Yes. Thank you.

By Trevor Freeman February 3, 2017 - 1:48 pm

This is excellent. Very, very excellent. Thank you.