Growing up I was called a ‘campus kid’ because my family lived in a house on the campus of Bishop’s University, an Anglican-founded institution located in Lennoxville, Quebec. My parents moved on campus shortly before I was born; I lived there until I was 18, at which time I took off for life overseas, eventually settling in Italy for 5 years before returning to Montreal. Those formative campus years instilled in me a (largely subconscious) respect for formal and institutional higher learning, which I have carried with me for most of my life.

Growing up I was called a ‘campus kid’ because my family lived in a house on the campus of Bishop’s University, an Anglican-founded institution located in Lennoxville, Quebec. My parents moved on campus shortly before I was born; I lived there until I was 18, at which time I took off for life overseas, eventually settling in Italy for 5 years before returning to Montreal. Those formative campus years instilled in me a (largely subconscious) respect for formal and institutional higher learning, which I have carried with me for most of my life.

A few years ago, feeling maxed out on the amount of graduate level education my spirit could handle, the respect that I once unquestioningly directed towards the Academy started to cough and sputter. Not only was I undergoing serious life changes that pulled me away from the path of formal learning; but also I was discovering the value of engaging and affirming informal, self-directed learning. I happened to encounter most of this through art-making, which I did both on my own and in an open studio community setting. I also met some new people with whom I gathered to read and discuss Julia Cameron’s Artist’s Way (which I am currently re-engaging again this year), a life-changing process that helps artists and creatives of any genre to work through their blocks. I should mention this period of self-directed ‘retraining’ coincided with important global events, such as the Arab Spring, the Occupy Movement, and more locally the so-called Maple Spring of student protests in Montreal. Like many, I watched almost all of these events comfortably from my laptop computer, contemplating and identifying with the motivations; yet admittedly insufficiently moved to join in with full gusto, if not in less overtly confrontational ways such as co-creating a grassroots DIY arts collective.

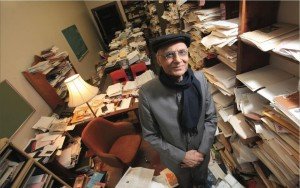

Looking back, included in this shake-up of standards and cultivation of personal indignation towards formal and traditional learning models was my discovery of the facebook page of Professor Arvind Sharma, McGill University’s Birks Professor of Comparative Religion, in September 2012. One day I noticed in my facebook feed a friend of mine had ‘liked’ one of Prof. Sharma’s posts: “Doubt is God’s way of disclosing a secret.” Short, sharp, and no citation or authorial attribution in sight. That felt pretty novel! I looked through the page’s timeline history and discovered other fresh expressions of interesting existential questions, all of which were Sharma’s own personal reflections. I was delighted to discover that a university professor 1) had found a way to use facebook beyond stalking and publicity 2) revealed personal insights uncorroborated by external authoritative support.

One day last month Prof. Sharma posted the following thought: “Just as there are contemporary answers to perennial questions, there are also perennial answers to contemporary questions.”

This stood out to me as a concise and accurate formulation of the challenge I continue to wrestle with as a member of a faith tradition/community who wishes to engage the tradition’s wisdom in ways that resonate with the context around me. I therefore contacted Prof. Sharma to ask if he would be willing to expand on this topic for the benefit of sharing his insights with the readership of this blog.

Technically, the daily thoughts that Sharma posts on facebook have grown out of a custom he initiated to help students in his World Religions class help to focus their mind. Each class would begin with a question for students to puzzle over and end with a ‘thought’ offered by Sharma.

Technically, the daily thoughts that Sharma posts on facebook have grown out of a custom he initiated to help students in his World Religions class help to focus their mind. Each class would begin with a question for students to puzzle over and end with a ‘thought’ offered by Sharma.

How do these questions and thoughts help us to focus our mind? Sharma gave me the example of the Greek scholar Archimedes who had a ‘Eureka’ moment in the bathtub when he realized that the mundane activity of sitting in a tub of water presented him with the solution to a problem with which he was given charge by the king of Syracuse. In short, all that we encounter is pulsating with answers to our most urgent questions provided that we are ready to read those questions and answers into and out of what surrounds us. Likewise, scripture can ready our mind to find solutions.

But what is scripture? Is it possible that anything, engaged repeatedly and intentionally over a long enough period of time, can serve an individual or community as scripture? Can you really “make the statements your child makes into scripture”? Sharma suggests scriptural value is fundamentally that which a person or community attaches to the (declared) source of the scripture–an investment of power transacted by many people.

Sharma is particularly interested in the process and outcome of employing and engaging all the ‘scriptures’ at one’s disposal. It is not a stretch for readers of the bible to see parallels in episodes and ideas between the Gospel books and the Book of Acts. Yet the same interaction can happen between the Bhagavad Gita and the Quran; the doctrine of karma and the serenity prayer used in the Alcoholics Anonymous recovery program; the concept of dharma and Rabbi Zusya’s claim that he would not be asked “why were you not Moses?” in the world to come.

Sharma finds a higher plane of existential discernment when studying and questioning two scriptures instead of just one, thereby “removing the invisible boundaries, the lines in sand–who has drawn those lines, anyway?”

Nesting within a religion can provide a secure foothold and the firm hand of authority along the journey; yet, ultimately, the seeker must always be prepared to move on (just as ‘the Son of Man has no place to lay his head’).

Perhaps intuiting that first thought I read posted to his facebook page, Sharma encouraged me to “honour what is doubt, for it prevents you from settling for second best.” Yet did Jesus not advise “if you have faith and do not doubt, you will not only do what has been done to the fig tree, but even if you say to this mountain, ‘Be taken up and thrown into the sea,’ it will happen.” Perhaps it is this to which Sharma refers when he claims that doubt should be cherished not feared for it will be removed with the advent of truth, for “truth is self-certifying.”

Whatever truths can be gleaned from his daily thoughts, Sharma contends these truths are reclaimed by the reader and have little to do with him: “it doesn’t matter what I have or had in mind but rather what you get out of it!” This is precisely what resonates with me as someone who has embraced to a large extent the path of informal, self-directed (yet collective) learning. Literally born and raised from within an authoritative institution, I (and many of my peers) now face the challenge of discerning authority as that source of truth which removes doubt on all levels: spiritually, experientially, intellectually, socially, etc. Can this challenge be met from within the confines of a religion? I find it hard to argue with Sharma that the “search for truth is scary because you cannot make any presumptions about what it will be.”

By Tony Houghton June 30, 2014 - 1:52 pm

Doubt is part of the Christian journey as seen even after the resurrection “Then the eleven disciples went away into Galilee, to the mountain which Jesus had appointed for them. When they saw Him, they worshiped Him; but some doubted.” There are several reasons for doubt but they should be used as a tool to reinforce faith . Why seek for answers in the Christian faith from a Hindu ,there are lots of Christian thinkers that could help you out such as J I Packer Ravi Zacharias R C Sproul Lee Strobel,etc

By Afra Saskia Tucker June 30, 2014 - 4:11 pm

Thanks, Tony, for the references. I agree that doubt is part of the Christian journey. I am familiar with Ravi Zacharias; I shall keep on the lookout for the others you cite.

I’d like to clarify that I did not initiate the conversation with Prof. Sharma because I felt a need to be ‘helped’ in the Christian faith by a Hindu (although Sharma teaches World Religions and therefore has an interesting and worthwhile perspective on Christianity to explore). Rather, as explicit in the topic I have chosen for my blog here on The Community website (My Faith in Your Faith), I am interested in interfaith dialogue opportunities and encounters, and I was interested to glean some insights on what Sharma may have had in mind when he wrote of “perennial solutions to contemporary questions” (which I wrote this in the posting). The angle on doubt emerged afterwards as I created the blog post and certain things I had not been aware of before came into focus. My aim in speaking to Sharma was to dialogue and converse, not to be ‘helped’ (although it was a helpful conversation); indeed my expectations were met, my perspective expanded, and I am thankful for the interesting discussion.

By Tony Houghton June 30, 2014 - 4:40 pm

I also came across a talk by D A Carson who had a talk on doubt ,a man who was raised in Montreal . His talk on doubt was quite interesting http://files.urc-msu.org/mp3/institute/DA06part1.mp3 Hope you enjoy this talk.